Parenting Conversation: When You Think Your Tween/Teen is Lazy

Django groen, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

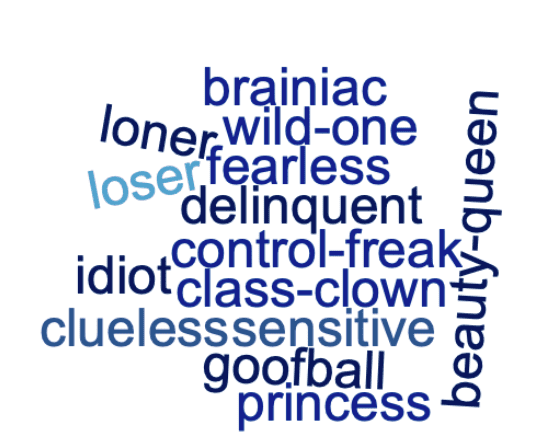

As school starts around the country for many kids, there will inevitably be struggles between parents and kids to get into the swing of things regarding time management and homework and effort. One of the most common things I hear about adolescents is that they are “lazy” and I think it bears exploring before we as parents/caregivers and educators go throwing that label around. There are a lot of reasons why our kids can struggle to find motivation to get things done, and it’s important for us to recognize the emotional weight many of them are carrying after the last two-plus years of uncertainty. Navigating the social world of adolescence, identity development, physical changes in their bodies, the impact of hormones, along with the news of climate change and wars in different parts of the world, uncertainty about Covid and monkeypox and the health of the economy can leave anyone exhausted and wondering how or why to get out of bed in the morning.

Add to that the fact that some kids just process information differently, and it may be that your child isn’t avoiding doing anything, but that they’re using so much energy just to move through the day that by the time they sit down to a stack of reading and other homework to do, they’re spent. Most parents want our kids to develop the ability to manage their time and energy and fulfill their responsibilities, but does calling them lazy motivate them to do that? (The answer is no – you can shame a person in to doing something for a short period of time, but it’s not an effective way to change motivation or behavior long-term – more on that in another post soon).

One of the first things I like to ask parents and caregivers to do before they address the idea of work ethic with their child is to spend some time with this worksheet I created. Getting really clear on where you developed your idea of what “work” looks like and why is a great starting point. It may be that as you go through this you discover many of the beliefs you hold about work are arbitrary or outdated. It may be that if you do this with your co-parent or parenting partners, you learn that you have some very different ideas. Kids with different learning styles (often called neurodivergence) can be doing a whole lot of invisible work that merits recognition. A child with ADHD who is struggling to sit still and pay attention in class is going to be expending a lot more effort than a kid whose primary learning style jives with the typical classroom setting. Expecting the same results from both of those students isn’t fair or practical.

Once you’ve spent some time with this questionnaire, sit down and talk to your child about it. What ideas have they absorbed from you about work? Where can you all begin to come to an agreement on what is important – effort, progress, results? Having a conversation about this can begin to shift how you talk about the way your child spends their time and whether or not they feel like they are being acknowledged.

As always, please comment and let me know your thoughts. If you want to dive more into this subject (and other parenting practices that will help you and your child strengthen your relationship), reach out via email and let’s set up a time to talk. kari@theselfproject.com