What if My Teen Hates Their Teacher?

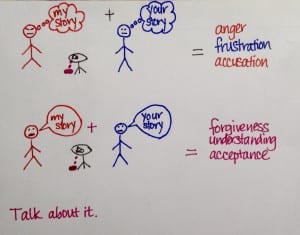

Without realizing it, we all put artificial limits on our view of the world and other people, and often this happens as a result of our emotional reactions to things others say or do. There is nothing wrong with having an emotional reaction, but it is what happens next – almost automatically – that can cause us problems.

When someone does or says something we don’t like, our brains quickly move from “I don’t like what she said or how she said it” to “I don’t like her,” which becomes, “I shouldn’t have to listen to her.” And then, because our brains like a complete puzzle instead of one with missing pieces, we set about justifying it by making a case that this person is ignorant or mean, thereby condemning all other interactions with them.

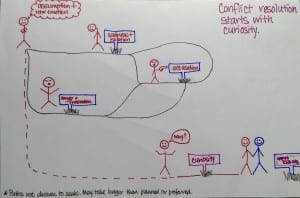

In terms of our kids, this can happen with respect to teachers in an instant. But in order to continually grow and learn, we have to expose ourselves to new ideas and new people. Just because we don’t connect with someone else on a personal level doesn’t mean they don’t have something to teach us. We don’t have to like them to listen to their ideas and see how they do things differently than we do, especially if we are going to have to sit in a classroom listening to them for months on end.

Often, students quickly come to conclusions about which teachers they like and don’t like, and those decisions have a great deal of bearing on whether or not they are willing to listen to what that teacher has to say. Helping students understand that whether or not we like someone personally is not necessarily correlated to how much they have to teach us is a valuable lesson that will serve them well as adults.

Thinking critically about the subjects or ideas that someone else puts forth regardless of how you feel about them on an emotional level is important because it can help us to consider different perspectives more objectively. It also keeps us from putting forth our own ideas in a way that feels like a personal attack. We all know that when we feel attacked or judged, we are less likely to share our own thoughts, and discussions can become more about winning or losing than an exchange of ideas.

Rather than letting distaste for one particular teacher become an excuse to disengage in a class, can you encourage your student to set aside their emotions in an effort to determine what they can learn from them?