Whether you’re a parent or an educator, the question of how to effectively discipline an adolescent can be tricky. Because these students are becoming more independent and our ultimate goal for them is to be able to make good decisions for themselves, it is important to set up a system of discipline that enables them to learn from their mistakes.

That is much easier said than done. Many of our traditional methods of discipline weigh more on the side of punishment than on they do on learning. As a parent, I have felt that sting of fear and anger that leads me to lay down a consequence that has a lot less to do with compassionate connection and gaining insight and than with retribution. While that is natural, it is also incredibly counterproductive.

The reason this kind of discipline is doomed to disaster has to do with the way the adolescent brain works under the influence of all those hormones. Once kids hit the t(w)een years, they experience:

- increased emotional responses (both number and intensity)

- less dopamine (feel-good hormone) secretion

- more feelings of isolation and separation from others

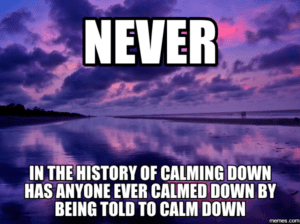

The more isolated and less happy we feel, the less we are willing to engage with others, which leads us to feel more isolated and more unhappy. It is a vicious cycle. And research shows that a brain saturated in emotion is less able to engage in the thought processes that lead to meaningful learning.

What this means is that if we catch our kids making a poor choice and immediately respond with strong emotion, we are only adding to the storm of fear or anger that they are feeling, and we are almost ensuring that they won’t be able to listen to us or learn from this mistake. Lashing out with shame, fear tactics, controlling behavior or even emotional withdrawal feels natural but can often turn a situation from a learning opportunity into what feels like a personal attack.

Now what?

You can’t talk your t(w)een out of feeling whatever they’re feeling (angry, scared, frustrated, sad), but you can acknowledge your emotions and let them subside in order to access your rational thought processes. (This is hard, no doubt about it – especially if there is yelling and door-slamming or words designed to hurt you. It’s important not to take your adolescent’s words or actions personally, even if they are aimed squarely at you.) Often, talking about how you feel is a way to help your student access their emotional vocabulary, too, and it creates connection between you.

You can ask lots of questions. Curiosity is the basis for learning, after all, and it may be that you both have something to learn from this situation. (Don’t be surprised if you ask why they made the choice they did and the answer you get is, ‘I don’t know.’ Often they don’t know. Move on. Ask about what they’re feeling. What they thought or hoped would happen when they made that choice.) If it’s not possible to have a thoughtful conversation in the moment, agree to separate for a bit and try later when emotions aren’t so high.

Do your best to separate the act from the person. This kid lied. This kid is not a liar. Labelling people by their behavior doesn’t offer room for learning or redemption. It puts them in a box that is really hard to emerge from.

Be clear about your needs and values. Do you need to know that this kid is safe? Do you need to know that other kids in your classroom/household are safe? Do you need to feel safe? Do you need to be able to trust this child? Is one of your highest values honesty? Compassion? Health?

Listen. When your student is ready to talk, let them. Talking can often help them diffuse strong emotions, understand irrational thinking, and create a feeling of bonding. Problem-solving together means they are availing themselves of your adult wisdom and it gives you insight into how you can best help your child begin to make better choices.

The more we can engage our adolescents in discipline, the better chance they have of learning from their mistakes, and the more connected they feel to us. Punishment creates separation and many t(w)tens already feel misunderstood and vilified. Talking to them about how they feel when they’ve messed up shows them that we are willing to be part of the solution, and that we expect them to be part of it, too.