Building Trust: Process Improvement Style

Whether you’re an educator or parent of adolescents (or both), you know that teaching kids this age is much different than teaching younger kids. As kids mature, they want more say in how things are decided, what the rules are, and how to determine where the boundaries lie. If we shut them out of the process, we risk them shutting us out of their decision-making, too.

Helping kids this age develop the skills to be productive, happy, fully functioning adults is part of our job, and including them in the conversations about rules and systems is messy but vital. So when you notice that something isn’t working (curfew or classroom norms or family routines), it can be helpful to embark on some process improvement work.

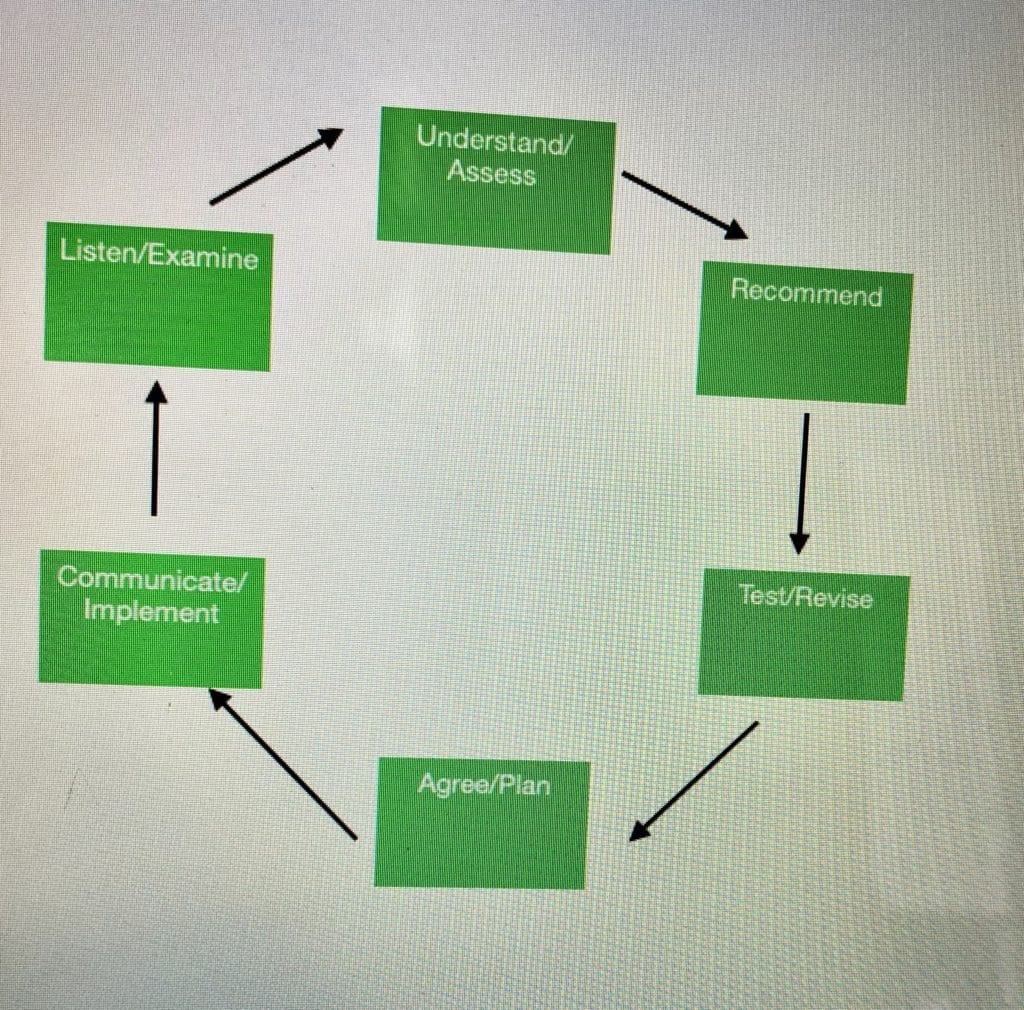

Each of these steps requires that all parties engage in a certain way in order to come to a better outcome. Everyone is an equal partner in this process, so building consensus is vital.

Understand/Assess requires everyone to lead with curiosity and a willingness to listen. It’s important to define what isn’t currently working and remind folks that just because something isn’t working doesn’t mean they’re to blame – it’s the process or system under scrutiny right now – not the individuals.

Recommend requires permission. Is everyone in agreement or ready to move forward with new ideas? Are there some folks who need to talk or listen more?

Test/Revise requires curiosity and a willingness to collaborate. This doesn’t have to be the final iteration – just an honest attempt to make things better. If everyone agrees to disagree with ideas instead of people, this will go more smoothly.

Agree/Plan requires honesty and dialogue. Where are the areas of alignment (what worked ok for everyone)? Where are the areas of divergence? Everyone involved should feel as though their ideas are equally important and their voices equally valid. Capitalize on the agreements to build a plan.

Communicate/Implement requires effort and careful listening. Does everyone understand the ground rules? Does everyone know what to expect as the new system is put in place? Does everyone have a role to play in setting things in motion?

Listen/Examine requires curiosity and honesty. If something isn’t working or anyone is feeling resentful or unheard, it’s important to know that. Are there unintended consequences of the new system?

If kids know that we’re willing to look closely at our rules and norms and engage them in a process of making things work better for everyone, they’re more likely to open up and feel empowered. Adolescents need to be reminded of their importance and the impact they can have in the systems that serve them as well as their responsibilities. Giving them opportunities to practice being part of the solution can often help diminish the amount of complaining and defiance they engage in and it helps them develop the skills they’ll need to work with others as they move farther and farther out in to the world. Adolescents are also often much more creative in their thinking than adults who have been entrenched in systems for years and it’s beneficial to us as parents and educators to be exposed to their ideas.

I’d love to hear how folks implement these ideas to change the way they do things with teenagers and get some feedback on how it worked.